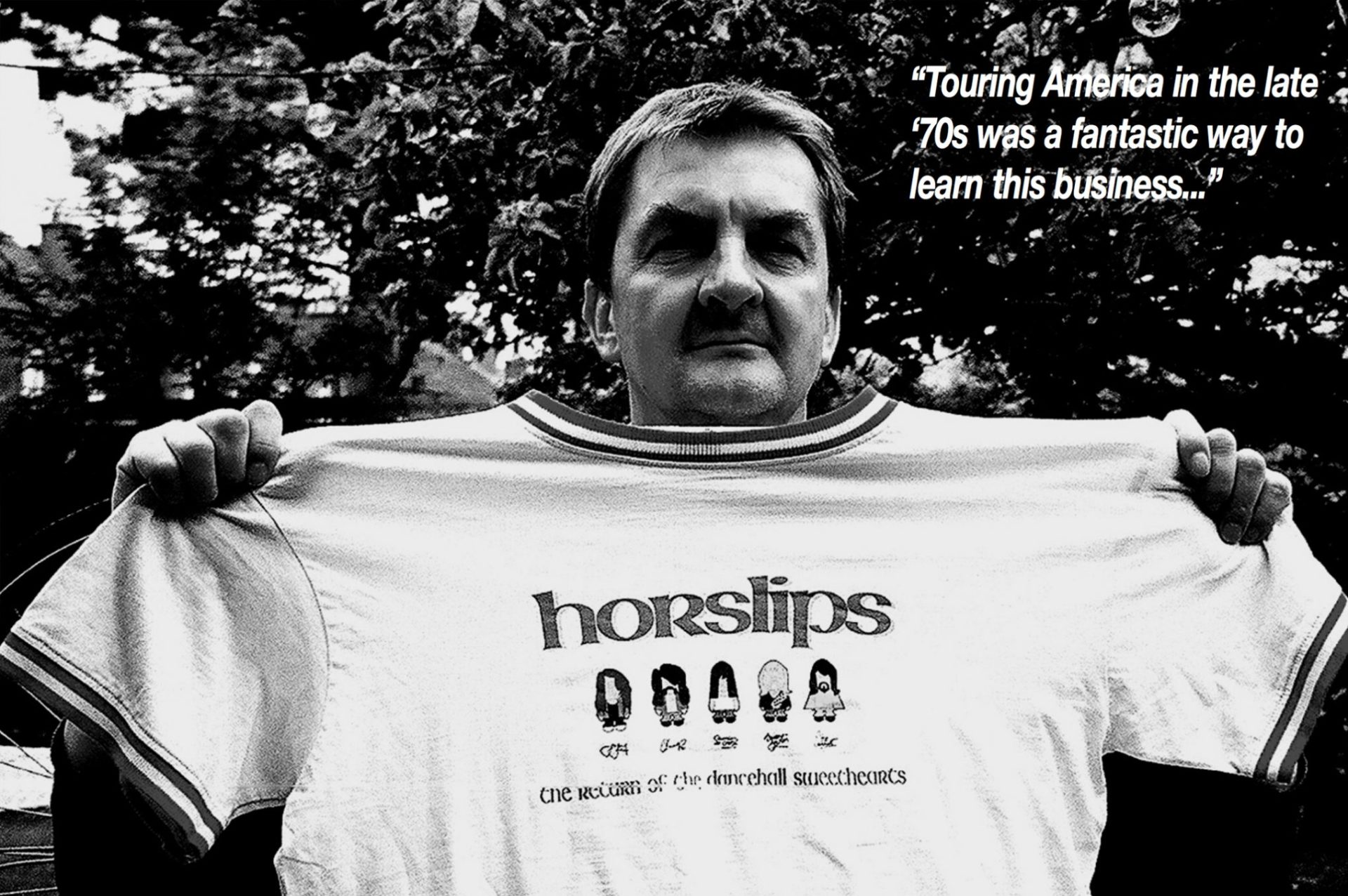

Steve Iredale

In the early ’70s, Ireland was in the middle of a social revolution. Whereas Elvis, Buddy Holly, Cliff & The Shadows and The Beatles had given the youth of America and Britain an identity and, at last, a voice, Irish teenagers had every right to feel they were behind the times. It wasn’t until the turn of the ’70s that Ireland gave birth to its own exportable rock’n’roll talent, in the shape of Rory Gallagher, Thin Lizzy and Horslips — a band who pioneered the fuzion of rock with traditional Celtic folk and produced a series of seminal albums that have remained cult classics ever since.

Someone who experienced this revolution first- hand, and later became part of it, was a young Steve Iredale — who started life as a music fan and grew to become one of the most respected production managers and touring consultants in the business.

Through his sister-in-law’s record collection and furtive listening to Radio Luxembourg, Iredale gained his first exposure to rock and pop music. Around late 1972, a friend played him a new track by Horslips, called ‘Furniture’, setting Iredale’s imagination alight.

“Horslips’ thing was to integrate traditional tunes within their own original rock songs, and ‘Furniture’ was an early example that featured ‘Ó Ró Sé do Bheath Abhaile’ lurking in the background in the song. That’s really when I got into music in a big, big way. I also got into Mott the Hoople, who I still love to this day but I never got to see them live because it was at a time when bombs started to go off in Dublin, and all the British artists cancelled their dates.

“But Horslips were the ones that were most accessible. They existed, they were Irish, they were

exciting and very different and, compared to what we were seeing regularly where I was growing up, they were a huge change.”

By the mid-’70s, Iredale had progressed from being a fan to actually working with Horslips. How did that develop? “Through being a nuisance, really,” he says. “Articles had been written about their famous Bedford truck with a big fist on the front [from the cover of their seminal 1973 album, The Táin], and the band travelled in a Range Rover, which all sounded very exotic to me. They came into town with six or eight guys, including Robbie McGrath and Martin Mulligan, with big beards, moustaches, long hair, flares and tie-dyed shirts, and I wanted to hang out with them, so I offered to help load equipment.

“I didn’t leave school until 1977, but in the couple of years leading up to then, my main objective during any summer holidays from that point on was to go and see them in as many places as possible, and help them out.”

Eventually, Iredale was offered a full-time job, initially as a backline technician, then later as the FOH engineer. “They were nice, genuinely nice people and, totally against my parents’ wishes, I knew this was what I wanted to do for a living. So I joined the Horslips crew in the summer of ’77. Back then, they had a wonderful Midas board, a 19-2 console with two-band parametric EQ, and it was previously owned by Greenslade. The PA was a Martin ‘building block’ system that was a beast of a thing to carry anywhere!”

Horslips broke the mould in the Irish dancehalls by taking the FOH control position midway down the hall,

as Iredale recalls: “It caused a bit of a problem because the way the migration of the audience went, this became an obstruction. There’s absolutely no way you’d get away with it now under the health and safety regulations, putting a barrier halfway down the hall. We ended up walling the console in with flight cases, like a sort of Fort Apache!”

The band gave Iredale his first experience of touring America. “I went to the States in my first year with Horslips and that was unbelievable, just arriving in New York, getting off the plane and going into Manhattan, and the next day being given the keys of a van and told to go to New Jersey to pick up new backline. I had to learn very quickly.

“Things we take for granted, like power, were big considerations once you crossed the Atlantic. Plus, you drove hundreds of miles before gigs, and got no sleep, but it was a fantastic way to learn this business.”

“I got a call one night from Tim Nicholson, who was the tour manager for U2 at the time, saying that Barry Devlin [Horslips’ bassist and later U2 video whoareyou director] had been talking with Paul McGuinness and recommending that we have a chat with a possibility of getting involved with U2. Touring around Ireland wasn’t appealing to me and the prospect of getting back to the US again or touring Europe did appeal to me. I started with them as backline tech, and I took a huge cut in wages. You also had the lottery of when you got paid with U2 at that particular point, because they were broke… as hard to believe as that may be now!

“My first job for U2 was to go to Heuston Station in Dublin to pick up Joe O’Herlihy. I’ll never forget to this day Joe’s words: ‘This is not your normal band’. I knew when he meant many years later and many times in the future.”

As the ’80s unfolded, Iredale graduated from backline tech to stage manager, and then to the role of production manager. One of the most productive exercises he ever did, he says, was to embark on a research project into the American production industry in 1985, prior to The Unforgettable Fire tour.

“I went there not only tosee what all the acts were doing at the time, but also to check out what all the suppliers were doing, who was doing the best work, and also analyse how venues coped with rock shows,” he explains. “I was put into an apprenticeship with Nocturne in San Francisco with Pat Morrow, Herbie Herbert and Benny Collins. Herbie was managing Journey were using video as part of massive productions, and they were the first people to get into the 360° arena show. It’s something that appealed and when you actually look into the economics of what was going on, with that 360° show and the possibility of generating an extra $1.5 million of income over the course of a tour, it certainly looked like the way to go.

“Willie [Williams] liked the idea and between us we sold the idea to Paul McGuinness who, in turn, sold it to the band. To this day, U2 continue to do 360° shows, and the people who probably saw the U2 show in 1985 from behind the stage are the same people who are watching it now in 2005.”

END OF AN ERA

U2’s current Vertigo tour is the first in 23 years not to benefit from Iredale’s experience. His absence has raised many an eyebrow within the industry and although a sensitive subject, I was keen to get his side of the story.

“Around 18 months ago, I made contact with the U2 office to find out from Paul what the future held. I wanted to tie things down because I had a few commitments coming up but my first preference was always to work with U2. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, we never managed to have that discussion. Promises were made to have it later on, and later on, but it never happened. In July 2004, I’d heard that Jake Berry was already working on the tour and I hadn’t been contacted about this, so I decided to try and find out what was going on. “It was only last September that I managed to have a discussion with Paul who said, ‘Well, we’re involved with ClearChannel again and we’d like Jake to take the tour forward — you’ve worked with Jake on the previous tour… would you have a problem with that?’.

“Accepting that I didn’t have a problem, Paul told me that my role would have to change. He said that the band wanted me to project manage the European leg, and put the outdoor project together, with the proviso that I would need to clarify this with Jake. Unfortunately, Jake’s appraisal of this situation differed and that’s where it all broke down.

“I went back to Paul, and he had Susan Hunter [from Principle Management’s office] e-mail me to say he would come back to me once he had a chance to speak with Jake. I’m still waiting for the call from Paul. Losing the job wasn’t as bad as them not making that phone call. After 23 years, it was very disappointing.”

I spoke to Paul McGuinness about this situation and asked him to make comment. He told me: “Steve is a wonderful professional — one of the best you would ever come across in the touring world. This is, however, largely a freelance industry and people come and go. That kind of freedom is one of the most attractive things about it for a lot of people. U2 have often changed record producers and sometimes we go back to them, as we’ve done with Steve Lillywhite. I’d like to think that we’ll work with Steve Iredale again in the future.”

In between U2 tours, and since his association with the band, Iredale has worked with a wide range of other artists and events. As well as working with Prince, George Michael, Bon Jovi and Metallica, Iredale co-ordinated Woodstock in 1994 and has managed various high-profile ceremonies and corporate events in Holland, as well as a string of top Irish projects. Robbie Williams’ huge open-air shows in 2003 were also aided by the Iredale touch.

“What I currently do is designed to suit the lifestyle I now have. I like the fact that I can get tours like Robbie Williams that last maybe three to six months, which means I can spend a lot more time at home. I do a lot of consultancy and corporate production work from here in the outskirts of Dublin, and it suits me fine. I’m involved with Coldplay in a consultancy role, now that they’re moving up to stadium status. Certainly if I liked the act, I would have no hesitation in taking on a position as production manager.”

A RARE COUPLE

Iredale and his wife Sue (a.k.a. The Duchess) are, like the Stickells and the Marshalls, among that rare breed of couples who have waved an influential wand over the live industry. They met in 1982 at a Lyceum show when Sue, part of the stage crew, informed Steve that

he was putting a snare drum skin on badly! They met again three years later at U2’s The Longest Day gig at Milton Keynes and a relationship grew from there. The Iredales were finally married 12 years ago.

The Duchess now runs productions for Denis Desmond and his MCD shows in Ireland. “She’s very good at it as well, I must admit,” says Mr. Iredale. “Trying to keep 23 outdoor shows in your head at the same time and juggle them all is quite a feat especially when some of the shows have more than 80 acts. We just get on, and when we happen to work together it’s very productive, although there have been a few fireworks when we have worked the opposite side of the fence.

“The first ever Robbie Williams show I did was at Slane Castle — it was his first-ever outdoor show and Sue was the promoter’s rep. It got so heated

that I had to change hotels. We both feel strongly about what we do and sometimes it clashed on that particular show!”

LOOKING AHEAD

Apart from the current Coldplay project, Iredale recently produced a live DVD and CD for Liam O’Connor, a gifted traditional player in a one-off performance with 13 other musicians in Killarney. At the start of 2005, he also teamed up with former U2 colleague Jake Kennedy to project manage the opening ceremony of Cork’s 2005 European Capital of Culture year. Next year is already looking busy as he looks forward to new projects with Tom Armstrong and Sightline Productions of Holland.

Outside of the industry, Iredale’s been busy coaching his son’s Under-14 football team who won the Division One league in their age group. He has also taken time out to embark on City & Guilds AutoCAD 2D and 3D courses which he hopes will augment his already invaluable production skills.

As we complete our chat over a pot of tea in his garden, Iredale, now 46, grins: “It’s been a crazy old life. I jumped from being a fan to a roadie and I’m still having a career… 28 years doing the same kind of thing. Not bad, really!”

Photography by Mark Cunningham